|

6. Shiprock and the

Los Alamos Mountaineers

LAM History Index |

Go

to Previous Topic |

Go to Next Topic Of the many natural

wonders within a day's drive of Los Alamos, Shiprock is perhaps the most

spectacular and mysterious. Over many years, Don Liska and other members

of the Mountaineers have been a large part of the history of climbing

Shiprock. During an exciting 2006 presentation to the Mountaineers, Don

described his role, and that of other Mountaineers, in the history of

Shiprock.

Fig.

1. Don and Alice Liska atop Shiprock

(Ernie Anderson photo, taken from a plane circling the peak, 10/14/67.

This photo also appears in Eric Bjornstad's book "Desert Rock.")

Don noted that Shiprock

was considered one of the 3 great mountaineering challenges in North

America during the 1930's (along with Mt. Waddington and Devil's Tower)

until it was finally climbed by a Sierra Club group in 1939. Don said,

"After coming to Los Alamos and joining the Mountaineers, we made Shiprock a major climbing objective for the club. I had first climbed

Shiprock in April 1959 [before moving to Los Alamos] barely 20 years

after the Sierra Club did the first ascent in 1939 and 7 years after

only the second ascent by Tom Hornbein et. al. in 1952. Ours was the

last party to climb the infamous 'Double Overhang,' first climbed by the

Sierra Club using ice pitons, just three weeks before Pete Rogowski

discovered the much easier 'Step Around' pitch. My 1959 climb continued

to hold me in awe of this famous edifice. Shiprock in those days still

represented an extremely attractive, wild and difficult climbing

adventure for would-be extremists, and many well known rock climbers

made the climb in the 50's and 60's, the same era when big wall climbing

in Yosemite was developing. The complexity and length of its route, the

number of ropes required by a pair of climbers to achieve a safe ascent

(four), the heavy loads of equipment and water, the potential for a dry

bivouac, the heat, etc. tended to ward off casual ascents. Perhaps

sparked by my own personal fervor there quickly developed in Los Alamos

a few climbers who became 'extreme Shiprock enthusiasts' such as Larry Dauelsberg and especially Ernie Anderson as prime participants but also

Mike Williams, Carl Keller, Eichii Fukushima, Larry Campbell, and Dave

Brown. I believe that fervor has cooled considerably in recent decades

and Shiprock today has become more of a 50 classics peak baggers

target."

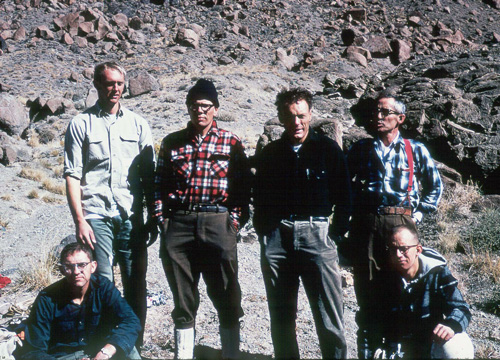

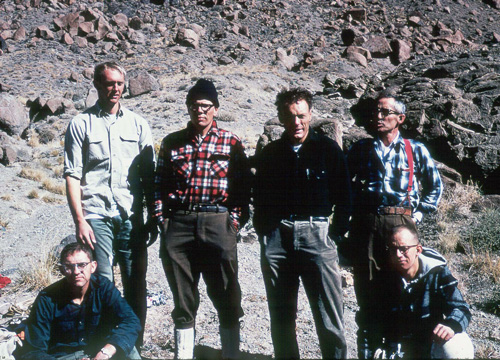

Fig.

2. Los Alamos climbers after the 106th ascent of Shiprock, 10/22/66.

Standing (L to R): Larry Dauelsberg, George Goedecke, Don Liska,

and Ernie Anderson. Sitting: L-Detzel, R-Breisch.

"Still, already by 1959

we were the 43rd party to summit Shiprock. In subsequent years, the

Mountaineers probably climbed Shiprock more than any other group did,

with perhaps 50 to 60 ascents. By the time of our third ascent in

October 1967 we were the 112th party to summit. On this climb Alice

Liska became the 15th woman to make the top, which in those days

frequently required a bivouac. In 1968 I joined Harvey Carter on first

ascents of many of the major towers that cluster around the base of

Shiprock. Some of these were more demanding than Shiprock itself and

most have not been repeated. Sextant, for instance, took us 3 days as

opposed to only 12 hours for the standard Shiprock route, once the way

is known. At any rate, over the years I have been involved in a record 9

ascents of the standard route."

"One early climbing partner, John Marshall, blessed Shiprock with the

moniker 'Shit-Rock' due to really bad rock at the mouth of the Honeycomb

Gully, which we explored at considerable risk. Even so it was here that

we one day found a camera that had plummeted down the gully at some time

past, fortunately with no body attached. It was badly smashed. The upper

Honeycomb Gully is the accident scene in Tony Hillerman's 'Fallen Man'

mystery novel."

Dave Brown remembers that Shiprock was one of the best trips he has ever

done with the Mountaineers. They did the climb in two days, with an

intentional bivouac. From there they saw the long shadow of Shiprock

stretching across the desert floor. He noted that "It's the only

mountain that you rappel down to get up, and jumar up to get down."

On October 12, 1969, the Mountaineers climbed Shiprock on the 30th

anniversary of the first ascent. Ernie Anderson organized this climb and

provided a summit register to leave on top. The climbing party consisted

of George Bell, Will Siri, Eiichi Fukushima, and Mike Hart. Will Siri

was a well-known Everest climber from Seattle, and a leader of the

Sierra Club. David Brower, who had led the first ascent in 1939, was

invited but could not come, so he sent Will Siri instead. Larry Campbell

and Mike Williams took movies of the ascent, but Larry says that the

film was damaged in processing. Eiichi believes that this was the last

climb of Shiprock before the accident the next spring that led to its

closure by the Navajos.

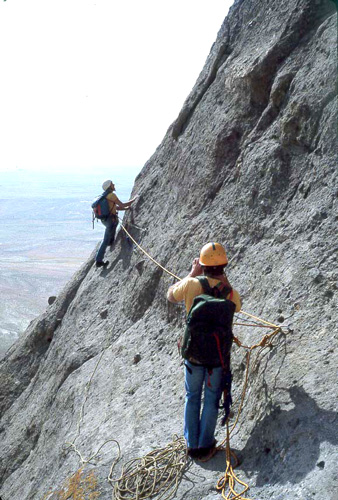

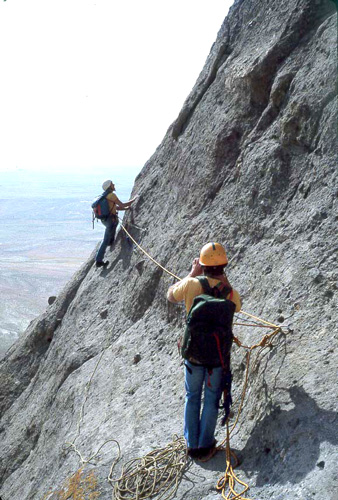

Fig.

3. Norbert Ensslin and Mike Fazio on the friction traverse, one of the

pitches where

a rope needs to be left behind on the way up to safeguard the return (D.

Liska photo).

Don Liska says that

"The accident on Shiprock that occurred during the period March 25-28,

1970 was arguably the most significant that the Los Alamos

Mountaineering Club was ever involved in. This accident culminated in

the official closure of the entire Navajo Reservation to climbing, a ban

which exists to this day. Prior to this, only Totem Pole and Spider Rock

had been placed off limits (after 1962) though the winds of change were

in the air and Shiprock had already claimed two lives in the 31 years

since its first ascent, so the traditional Navajo fear of death

therefore entered into the closure decision. With increasing traffic by

climbers, this decision was nearing a critical stage in 1970." Don

Liska's description of the accident is summarized below. (It is also

reported in the American Alpine Club's 'Accidents in North American

Mountaineering", 24th annual report of AAC Safety Committee, 1971, pp

8-11.)

"On Thursday March 26, 1970 a three-man party consisting of Jim Smith

and Bill Bull, both from Boulder, and George Andrews from Menlo Park

started up the standard route on Shiprock intending to climb to the main

(north) summit that day, bivouac at the 'U-Notch' below the Horn pitch

that night and climb the south summit on Friday before descending. There

was a second party at base camp as they left, including Don Liska and

Larry Dauelsberg of Los Alamos, along with Bill Hackett of Las Cruces

and Dave Beckstead of Colorado Springs. We intended on scouting a new

and difficult direct aid route up the west face of the rock to the

'U-Notch' where the first party was intending to bivouac. Our route was

totally pioneering and we had little idea of the time required to reach

the notch or of the difficulties along the way. We expected two or three

bivouacs."

"The weather that day was overcast with a forecast of clearing. As the

Smith party broke camp early on Thursday we briefly discussed their

climb and the first premonitions of possible difficulties arose when

they informed us that they did not intend to leave a handline at the

friction traverse, a steep, tricky, and exposed 125' pitch on the east

face of the rock below the second rappel. Since two of our party had

several times climbed Shiprock and knew all its hazards we warned them

that the traverse could be a difficult place to retreat across in wet or

snowy conditions. Then we parted and went our separate ways. We started

up our route over the 'Nest' and placed our first bivouac at the base of

the huge west wall where direct aid climbing was to begin. About 1 AM

early Friday a fast moving cold front out of the NW caught both climbing

parties high on the peak in their respective bivouacs."

"As we learned later, the Smith party had in fact not reached anywhere

near the U-Notch but had bivouacked on the chockstones below the first

rappel on the east face, just under the 'Colorado Col.' We, however,

were caught above the 'Nest' and covered in a deep blanket of wet snow.

As soon as daylight allowed, we began a series of rappels off the face

abandoning most of our equipment in a hasty retreat. We reached the base

of the rock about 600' below by 10:30 AM. By this time a foot of snow

blanketed the desert and enshrouded Shiprock and the storm continued.

For now, our major concern was our own retreat from Shiprock but we

began to realize that the Smith party might be trapped in a very

precarious position if they indeed had reached the 'U-Notch' for their

bivouac and had not protected their retreat across the friction traverse

with a fixed handline. As it turned out, the Smith party was in a much

more favorable position at this point but they still faced a desperate

situation ahead."

"Our fortunes picked up unbeknownst to us with the arrival the night

before of a second climbing party while we were in bivouac. An old

climbing pal Reed Cundiff (who did the first ascent of the SW ridge of

the Needle in the Sandias) and his climbing partner from Las Cruces

arrived in a VW intending their own climb of the rock the day the storm

arrived. The six of us now teamed up to pursue what we had reason to

believe could be a very serious rescue emergency of the Smith party.

Fortunately Reed had a VW and with its rear engine weight and the five

of us jumping on the bumper and pushing, we were able to work the

vehicle through the 5 miles of deep snow to the Red Rock 'highway' and

we then sped to the town of Shiprock freezing cold and mud-spattered.

With four jammed inside the car, two of us sat on top with our feet

through the sun roof barely hanging on as the sleet and wet snow

continued."

"A Navajo tribal cop soon stopped us but gave full cooperation when he

learned the details of our predicament. He escorted us into Shiprock

where we took a motel room and called Los Alamos for more LAMC help, and

Ernie Anderson, Eiichi Fukushima, and Bill Gage set out for Shiprock. In

the meantime, the tribal police drove Cundiff and partner to the Rock in

a 4WD to reconnoiter. Cundiff reported difficulty in even reaching the

top of the talus near the start of the route. He did not see signs of

the Smith party though as things turned out they were within 500' of

them at that point." [An interesting sidenote to this story is that the

cop that pulled over the LAMC party was Nick Saiz, the same state

trooper that was shot and wounded in the 1967 raid on the courthouse in

Tierra Amarilla. This event made national headlines at the time and was

often on the minds of later Los Alamos Mountaineers as they traveled

through Tierra Amarilla on the way to climb the Brazos Cliffs.]

"That evening as the storm was beginning to abate and the temperature

was dropping rapidly, Liska and Dauelsberg returned to the rock with

Navajo Tribal Authority 4 WD's, radios, etc. hoping to make contact with

the Smith party. They found Smith and Bull wandering dazedly near their

vehicle, disoriented and hypothermic. Smith was bleeding and both were

hurt and shaken. They reported their party had fallen and they had to

leave Andrews 150' above the 'Cave Pitch' (the first pitch) in the Black

Bowl near the Topp memorial plaque. Liska and Dauelsberg saw this as a

relatively straightforward rescue and radioed the other two climbers

still at the motel to come on out. By 11 PM under clear, cold skies we

were all gathered ready to attack the climb with a Stokes litter, first

aid kit, radios, lights, and essential climbing gear. Icy talus and snow

hampered the way."

"It turned out that Smith and Bull had left a 300' reepschnur on their

last rappel to the base. We found this rope indispensable in allowing us

to prussik up the difficult Cave Pitch and its now icy overhangs to the

scene of the accident some 200' above the base of the rock. We reached

Andrews around 2 AM and administered aid to his broken shoulder. We

loaded the hypothermic and pain-ridden victim in the litter and lowered

him over the overhangs to the base where he was man-hauled a very rough

half mile over icy talus to the waiting vehicles."

"As everything settled down, we learned that Smith and Bull had been

taken to Farmington before midnight on Friday evening for treatment.

Smith had a broken nose, jaw and cheekbones and required stitches for a

deep cut over his eye. Bull had bruised and battered ribs. Andrews

arrived in Shiprock by 6 AM Saturday as he began going into shock. He

was given intravenous glucose and then taken to Farmington where they

found he had a fractured elbow, broken shoulder, cracked ribs, a

concussion, and frostbitten toes. He was treated and then flown back to

California."

"This was an important rescue, though we didn't realize how critical

until several of us returned a week later to retrieve our gear and study

the accident scene. Shiprock was still somewhat ice and snow covered but

now quite climbable. Our team split up, part to retrieve gear left

behind during our precipitous retreat the week before and the others to

climb the normal route to the point where the accident occurred and do a

"forensic" search for technical evidence of the accident. When our

recovery team descended with the recovered gear, a tribal policeman was

waiting for us at the trailhead. He informed us that we were under

arrest, as Shiprock had been officially closed to climbing immediately

following the accident. In fact, the entire Navajo reservation was now

so banned. When we explained that we had been the rescue team and were

retrieving gear, he relented but still ordered us off the rock ASAP. Our

second team now descended with all the evidence they had recovered and

we left the area."

"In piecing together the details of the accident itself, along with

correspondence from the Smith group, we deduced that the Smith party had

spent a miserable bivouac on Thursday night below the upper prussik

pitch in the Rappel Gully with snow cascading down the surrounding rock

faces on top of them. At 7 AM on Friday they left their bivouac and took

4 hours to complete the 75' prussik up to the Colorado Col using their

only functional Jumar and one Hiebler ascender. They then completed the

120' rappel down the upper west face into the west gully and scrambled

down to the grey basalt water gully where they continued their rappels

on the 300' reepschnur anchored to a single piton. Here Smith rappelled

first and made it down OK. Andrews followed but after 100' the anchor

pulled out and he fell another 100' down the gully and off the steeper

bottoming cliff, crashing into Smith and causing the bulk of Smith's

injuries. In the tumbling fall Andrews also suffered most of his

injuries. Andrews had lost his helmet earlier that day and that may have

been the cause of his concussion. It was now 3 PM and still snowing.

About this time Cundiff had reached his high point but was unable to

make contact with the Smith party. Now Bull was stranded above with only

an old 120', 7/16" white nylon 'army surplus' mountain-lay rope of

dubious and well worn history. He drove in several pitons as a secure

anchor and rappelled off finding himself still almost 80' above the

others at the end of this short line. Under Smith's directions, he

climbed 25' back up the gully and cut off two strands of his three

stranded laid rope, giving him an extra 50' of line. He tied this extra

length to the uncut third strand and continued down. Considering the

skill with which Bull had managed this difficult maneuver (shades of

Tony Kurz on the Eigerwand in 1936), it's a pity that as he neared the

end of his 'rope' still 30' off the base, the uppermost single strand

parted about 7 feet below the two-strand cut line. Down plummeted Bull

to the base where he damaged his ribs by again crashing into poor Smith

who broke his fall. The LAMC team who studied the accident scene found

the uppermost strand to have partially melted against a sharp flake but

also to have a single-strand strength of only 350 pounds due to its age

and wear condition. A new rope's single-strand strength should have been

about 1500 pounds. At this point, very late in the day, the injured pair

of Smith and Bull administered what first-aid they could to Andrews,

re-anchored the reepschnur and finally rappelled to the base of Shiprock.

Staggering back over the talus towards their vehicle they were

fortuitously found by the Los Alamos climbers."

"In succeeding events George Andrews, a very big San Francisco corporate

lawyer, became an advocate of LAMC for its rescue efforts. Meeting him

years later in his huge law offices, he expressed undying gratitude to

our club and related that the Shiprock event was the highlight of his

outdoor life. He died in 1989. Somehow the rescue was reported to higher

officials and Dauelsberg and Liska were awarded with Documents of

Commendation from then President Richard Nixon. At the time we reacted

negatively to these awards due to the political climate that existed at

that time, but we have since come around to valuing these awards which

now represent to us the finest spirit of selfless search and rescue

efforts by willing volunteers. How these commendations ever came to us

and who recommended them in the first place has never been ascertained."

"The accident resulted in the permanent closure of the Navajo

Reservation to all climbing, a ban which still applies. However,

climbing Shiprock will not cease since it is considered one of the '50

classics' in Alan Steck and Steve Roper's 1979 'Fifty Classic Climbs of

North America.' The authors reiterate the climbing restrictions and

suggest that negotiations could possibly mitigate the ban. This has been

tried repeatedly and always failed since the ban persists." [Eiichi

Fukushima recalls that, right after the closure, the Mountaineers

contacted the Navajo Nation offering to train Navajos for climbing and

rescue activities, in the hopes of having the Reservation re-opened to

climbing. However, this didn't work.]

Don Liska noted that "The climbing ban was officially broken once, in

1975, by the Navajos themselves during the filming of 'The Eiger

Sanction.' Then they allowed Eric Bjornstad and Ken Wyrick from Moab to

climb the Totem Pole one last time to prepare the summit for the

helicopter film crew and remove existing ascent hardware and all traces

of prior climbs. Incidentally the tribe also received $40,000 for this

'relaxation' of their own rules. In Alpinist X, Bjornstad reveals that

the Totem Pole continues to be climbed, but by its hidden back side

'Bandito' route. Similarly, all climbers who adhere to the desirability

of the Fifty Classics will continue to find a way to circumvent the ban

on Shiprock, most by simply ignoring it. In fact, more climbers ascended

Shiprock in the 15 years after the ban than in the 31 years preceding

it."

LAM History Index |

Go

to Previous Topic |

Go to Next Topic

.

|